Many of you may already know about the flight and fight rest and digest state of the body, but did you know that there are ways to measure how “fit” these systems are?

To my surprise there is a wealth of research on how the nervous system is correlated with patterns of social and emotional behaviors.

Knowing more about the autonomic nervous system will help you understand the behaviors of the children you see.

How do you know if a child is dysregulated and if their nervous system has anything to do with it?

Recognize these kids?

- They easily meltdown or tantrum (this might occur daily)

- They are constantly “on the go” or unable to physically settle down or relax

- They may appear constantly worried, stressed or anxious

- They have difficulty calming down long after a stressful event

- They have difficulty sleeping

- They perceive typical sensory input such as touch as pain

- They have more frequent stomachaches

These are signs of a dysregulated autonomic nervous system.

The Autonomic Nervous System

Review of the nervous system. There is a part of your nervous system that is voluntary and a part of it that is automated and mostly unconscious.

The automated part is called the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

The ANS takes care of your basic needs. It is the reason why you don’t have to remember to digest your food.

It also protects you when you are in life-threatening situations by giving you that jolt of cortisol and adrenaline to get away from predators or swoop your child up from nearly killing themselves (again).

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) can be divided into two systems:

- Sympathetic nervous system (fight and flight survival state)

- Parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest state) (Lebouef et al, 2021)

Some also call this “the pause and plan” state which is also fitting as being in the parasympathetic state allows us to relax and mentally prepare for the future.

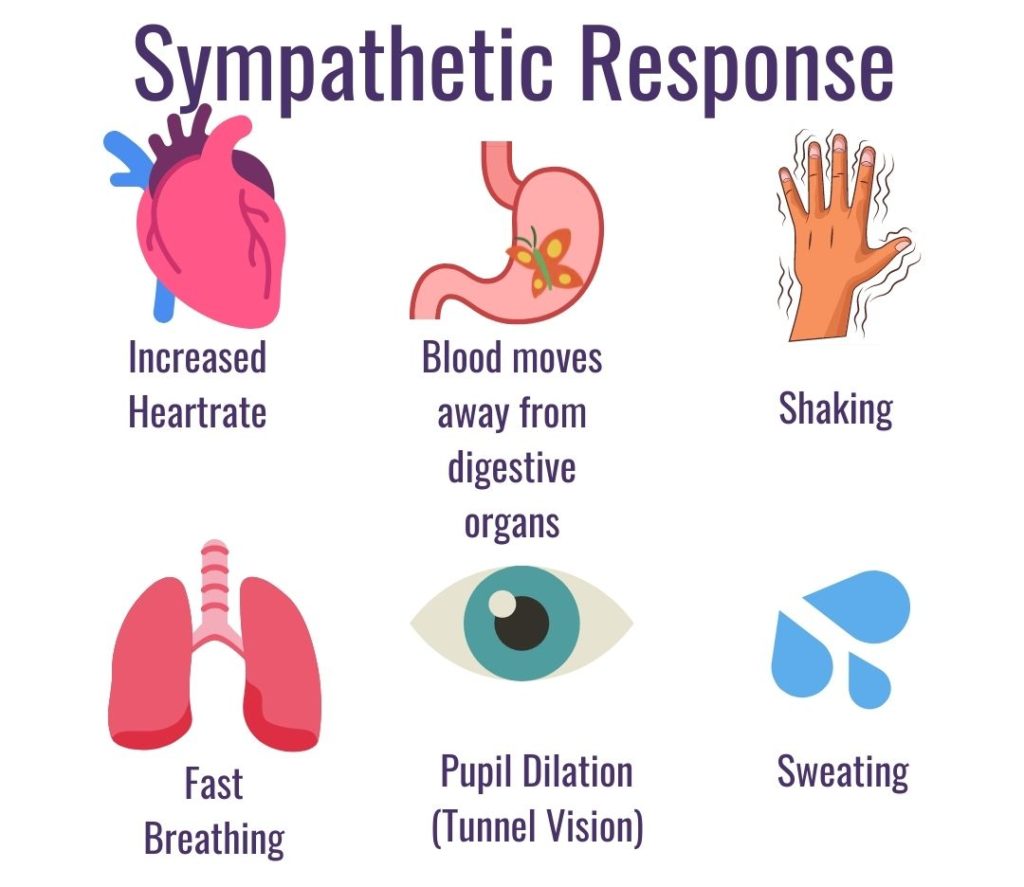

The sympathetic nervous system

Imagine that you were walking on a hike and you found yourself face to face with a live bear. Your body should trigger these sympathetic system responses:

- Increased heart rate

- Rapid breathing

- Stomach “butterflies” as blood moves away from digestive organs towards the limbs

- Constriction of most blood vessels and increased blood pressure

- Pupil dilation

- Sweating

- Dry mouth as the glands responsible for salivation are inhibited

- Release of stress hormone cortisol (Alshak & Das, 2020)

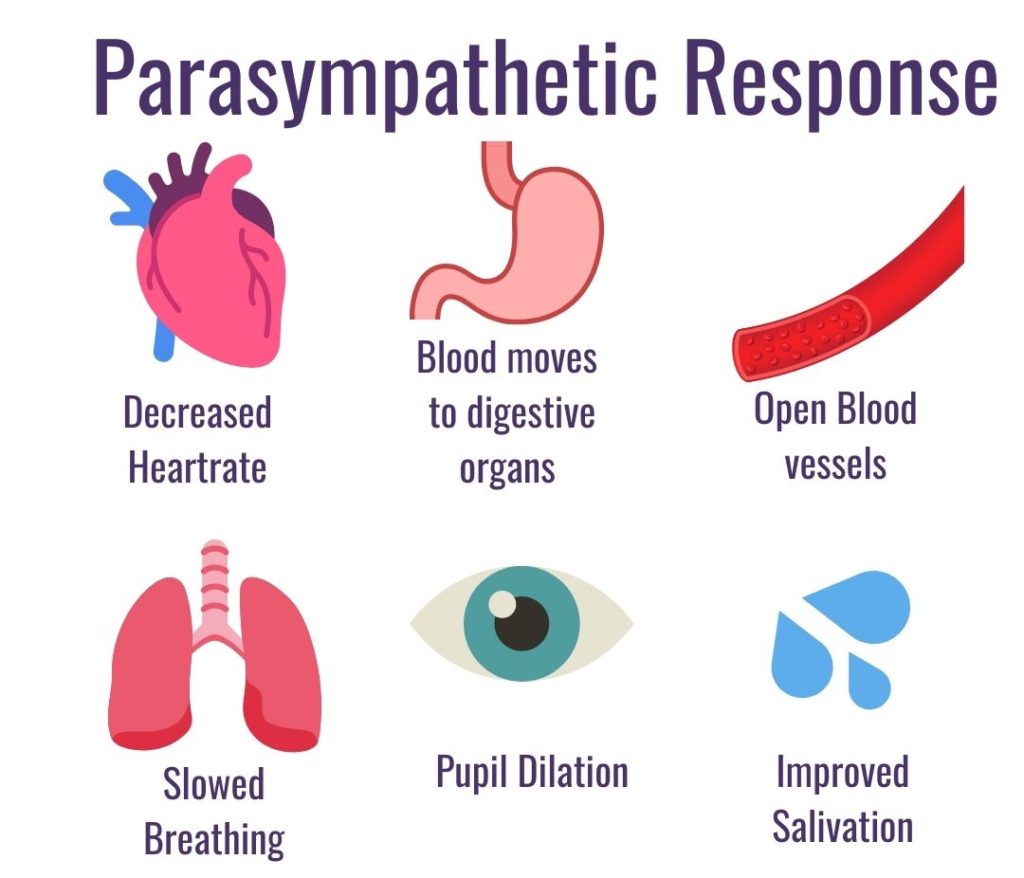

The parasympathetic (rest and digest) state

What is the body doing when not in flight and fight mode? The parasympathetic state is the counterpart of the sympathetic state.

Physical Markers of the Parasympathetic state:

- Decreased heart rate

- Improved digestion

- Relaxed and opened blood vessels

- Constriction of the pupils improving near vision

- Improved salivation

In a nutshell, when a child is calm and relaxed you can guess they are in a parasympathetic state.

The Body Brain Connection

Just as your brain can communicate to your body, your body can also communicate to your brain.

To discover why the body can influence your emotional state recall that your systems of respiration, heart rate and emotional regulation are connected by the vagus nerve.

In fact, the vagus nerve is 80% composed of highways back to the brain (afferent information). It is only 20% composed of efferent signals going from the brain to the body.

Therefore, more information is going from the body to the brain than vice versa. (Alshami, 2019)

The vagus nerve is the primarily responsible for the parasympathetic system. This nerve is pivotal to the parasympathetic state activation. The term Vagal Tone- describes the functioning of the vagus nerve to turn on the parasympathetic the rest and digest system. (Tindle & Tadi 2020).

Triggering the sympathetic state

Not only can the environment start the fight and flight response, the sympathetic state can also be triggered by emotions or memories such as thinking about something stressful or a traumatic event (Sokolov, 1963)

Just remembering a moment that was perceived as threatening can cause the same physical responses.

This is people can have memories of a disturbing event that cause night sweats and rapid heart rate.

Maybe just thinking of taxes has your chest tighten.

You most likely work with children behave in similar ways, especially children with sensory processing difficulties.

For example, some children can have such a stressful experience with a fire alarm that any other loud sound triggers increased heart rate, rapid breathing and crying.

See the blog on the fear paralysis reflex to see how a heightened startle response can trigger increased physical responses to benign sensory input like a loud sounds.

One study found that 2-3 year old children who had a tendency to withdraw from unfamiliar experiences, such as new social situations, tended to have increased salivary cortisol (stress hormone) levels and increased eye pupil sizes.

The authors suggested that these kids were showing increased sympathetic activity and also that they had a lower threshold for unfamiliarity and challenges. They differed in the pattern of heart rate on a measure called heart rate variability (HRV). (Kagan et al, 1987)

What is heart rate variability (HRV)?

One way that researchers have been measuring the strength of the parasympathetic system is using heart rate variability (HRV).

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is a number is obtained by measuring the variation of time between heart beats.

Higher HRV typically indicates a healthier person, both physically, and as researchers are finding, psychosocially as well. (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014)

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and Kids

High HRV is also being found be correlated to social-emotional and physiological strengths with children.

This measure was associated with increased social-emotional resiliency of children through difficult life events such as divorce of parents, decreasing the likelihood of future behavioral problems. (El-Sheikh, 2001)

The work of Porges found that infants with decreased HRV had greater behavioral problems at 3 years of age. (Porges, 1992)

Anxiety and depression are also significantly associated with decreased HRV in adolescents (Billman et al, 2019)

*Most of these examples are from a review article Krishnamachari Srinivasan, MD wrote about the connections in heart rate variability and dysregulation found here (Srinivasan, 2007)

The Autonomic Nervous System and Behavior

Research is finding that the strength of a child's parasympathetic system is correlated with other factors such social dynamics and problematic behavior.

For example, anti-social adolescents were found to have poor parasympathetic regulation of their heart rate in relationship to respiration. This was regulated by the vagus nerve.

These researchers found that in these subjects, anxiety was linked to the increased sympathetic activation of the heart rate. (Mezzacappa et al, 1997)

This is not to say that the parasympathetic state is ideal for all times. A healthy nervous system should be able to switch from either system appropriately depending on the environmental demands.

Researchers have been finding a correlation between low resting heart rate and childhood disruptive behavior. (Kindlon et al, 1995)

Another study found a connection between lower resting heart rates in adolescents as predictive of criminal acts in adulthood.

Under-arousal of the autonomic nervous system was theorized to be the cause of the low resting heart rate pattern of kids in this longitudinal study. (Raine et al, 1990)

It is crucial skill to be able to move between sympathetic and parasympathetic states or slow and fast heart rates. Being stuck in either high or low heart rate is indicative of difficulties with the autonomic nervous system (ANS).

Imagine the body as a car: the sympathetic system is the accelerator of a car and the parasympathetic system are the breaks. If someone is always riding the breaks they will need to be constantly revving the engine to move. (DePace, 2019)

The term “sympathovagal balance” describes the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems and the autonomic state resulting from the balance. (Goldberger, 1999)

Note on a more serious medical condition: Dysautonomia

Dysautonomia. This is a “group of complex conditions that are caused by a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS)”

To familiarize yourself with this diagnosis you can see this handout.

What is interesting to note is that these kids may have strong sensory sensitivities to, “noise, lights, odors and tactile sensations” (p 10).

As OTs, it is good to know how to spot a child with this possible problem especially if they are referred for sensory integration therapy.

Many of the signs and symptoms involve heart rate and blood pressure irregularities (such as orthostatic hypotension or the feeling of faintness upon standing).

Refer these children to their physician.

For the majority of the children we see the difficulties in autonomic system regulation may be more subtle.

What kids stuck in a sympathetic state might look like in the clinic

From my experience as an occupational therapist, I notice that kids are more picky about what kinds of hands-on therapy work in the sympathetic state

The kids appear more touchy and less tolerant of activities such as working on specific reflex integration points. They are also more likely to perceive touch as pain.

Sensory-motor activities such as crashing and other deep pressure input helps many of these children before they can tolerate more hands-on integration work.

Kids that Enjoy the Sympathetic State

One other important thing to remember is that children can be happy and excited in a sympathetic state.

Have you ever enjoyed the heart racing feeling of an action film or scary movie? The healthy individual is easily able to transition from sympathetic to parasympathetic states.

Though it may look like kids are enjoying themselves in a sympathetic state it can be easy to over-do these activities. (This might happen when a child is being tickled or in a pillow fight for example).

Be sure to watch high pitched squeals, sweating and other signs that a child is in the sympathetic state.

I also look for face flushing and the pace of the breath. Is it rapid and shallow or labored?

Being in this state is not a problem however a child may suddenly slip into the fight mode (feeling defensive) or accidentally slam their bodies into a hard piece of equipment or wall (this has happened in some of my sessions when I was not being observant of these cues).

How to change our state

In cases where there is no actual source of threat, changing our mental focus is just one way to alter the stress response.

For example one technique is to list “five things you can see, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste.”

This tool and others that change our thoughts, focus , perceptions and beliefs are what are nicknamed “top-down strategies.”

These techniques can train the upper portion of our nervous system or the prefrontal cortex. This part of the brain is like the CEO of a company.

HRV is connected to prefrontal cortex activity. The prefrontal cortex can manage the lower systems such as the limbic system and the brainstem to manage the autonomic nervous system. (Lane et al, 2001)

See the blog on the hand model of the brain for a simple review of brain structures such as the prefrontal cortex.

Why do my kids struggle to use their tools in the moment they need it most?

The problem I see with many adults is that we only remind kids to use these strategies when they are already in a dysregulated state.

For example, if you only wait till the meltdown to ask a child to choose a sensory strategy it is like waiting for the competition to start training.

Additionally top-down strategies, are very important however they should NOT be the ONLY tools in your tool bag or you will quickly find yourself frustrated and burned out.

Bottoms up!

Bottom-Up strategies are ones that address the body to mind connection such as reflex integration and sensory processing integration.

It is important to have an arsenal of both top-down and bottom-up strategies as 80% of the information traveling in the vagus nerve is going to the brain.

See our blog on emotional regulation for a simple bottom-up strategy.

Reminder that kids (and adults) need to practice both top down and bottom up techniques regularly before they are needed. More tools are on the way.

Thanks for checking out this blog! RSVP to a lecture on how to choose what top-down and bottom up strategies to use for teaching kids emotional regulation.

Thanks for subscribing and sharing.

Jasmine Erazmus OTR/L

References:

Alshak MN, M Das J. Neuroanatomy, Sympathetic Nervous System. [Updated 2020 Jul 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542195/

Alshami AM. Pain: Is It All in the Brain or the Heart? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019 Nov 14;23(12):88. doi: 10.1007/s11916-019-0827-4. PMID: 31728781.

Billman, G. E., Sacha, J., Werner, B., Jelen, P. J., & Gąsior, J. S. (2019). Editorial: Heart Rate Variability and Other Autonomic Markers in Children and Adolescents. Frontiers in physiology, 10, 1265. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01265

Dr. Nicholas DePace M.D., (2019, November 2) OVERACTIVE SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM, Franklin Cardiovascular Associates Autonomic Dysfunction POTS Center.

El-Sheikh M, Harger J, Whitson SM. Exposure to interparental conflict and children’s adjustment and physical health: the moderating role of vagal tone. Child Dev 2001; 72:1617-1636.

Goldberger JJ. Sympathovagal balance: how should we measure it? Am J Physiol. 1999 Apr;276(4):H1273-80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1273. PMID: 10199852.

Lane RD, Reiman EM, Ahern GL, Thayer JF. Activity in medial frontal cortex correlates with vagalcomponent of heart rate variability during emotion. Brain Cog 2001; 47:97-100.

Kagan, J., Reznick, J. S., & Snidman, N. (1987). The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child development, 58(6), 1459–1473.

Kindlon DJ, Tremblay RE, Mezzacappa E, Earls F, Laurent D. Longitudinal patterns of heart rate and fighting behaviour in 9-12 year old boys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:371-377)

Mezzacappa E, Tremblay RE, Kindlon D, Saul JP, Arseneault L, Segun J, et al. Anxiety, antisocial behaviour and heart rate regulation in adolescent males. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997; 38:457-469.

Porges SW: Vagal tone: A physiologic marker of stress vulnerability. Pediatrics 1992; 90:498-504.

Raine A, Venables PH, Williams M. Autonomic orienting responses in 15-year old male subjects and criminal behaviour at age 24 years. Arch Gen Psychaitry 1990; 47:1003-1007.

Sokolov E. N., Waydenfeld S. W., Worters R., Clarke A. D. B. (1963). Perception and the Conditioned Reflex. Oxford; New York: Pergamon Press Oxford

Srinivasan K, Vice Dean, St. John’s Research Institute, Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2007; 3(4): 96-104 https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ942527.pdf

Tindle J, Tadi P. Neuroanatomy, Parasympathetic Nervous System. [Updated 2020 Nov 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553141/